Document Parsing with Nougat: Transforming Scientific PDFs into Machine-Readable Text

Table of contents

Introduction

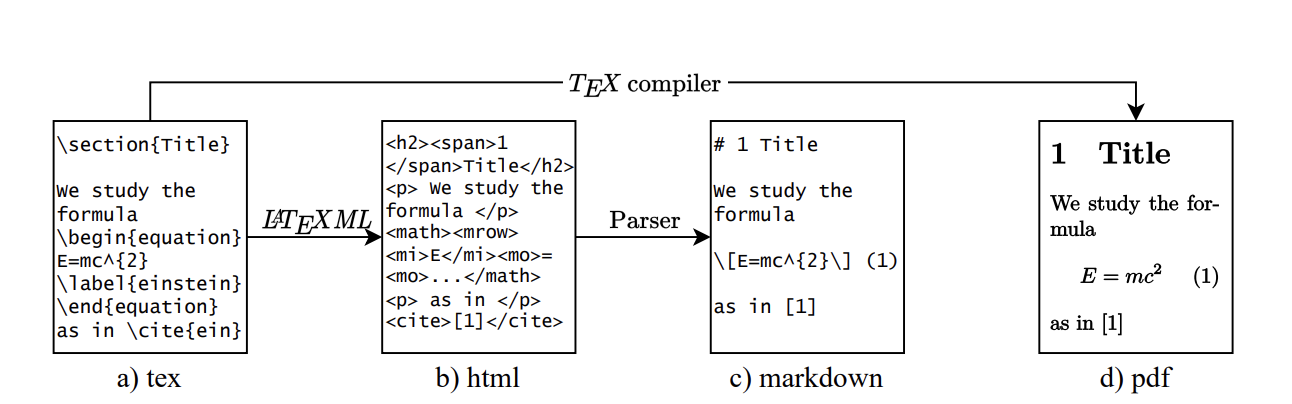

Scientific knowledge today is largely locked inside PDF documents—a format optimized for human readability but not for machine understanding. Extracting information from PDFs is notoriously difficult because they lack semantic structure, especially when dealing with complex elements such as mathematical equations, tables, and figures.

This is exactly the challenge that Nougat (Neural Optical Understanding for Academic Documents), developed by Meta AI, is designed to address. Nougat is a state-of-the-art model that converts scientific PDFs into structured, machine-readable text. Unlike conventional OCR systems that treat text line by line, Nougat captures the relationships between elements on a page, allowing it to handle the intricacies of research papers—mathematical expressions, tables, and complex layouts—with remarkable accuracy.

In this blog, we’ll dive into how Nougat works and how you can use it to parse scientific documents and extract structured outputs—including equations and formulas—from PDF files.

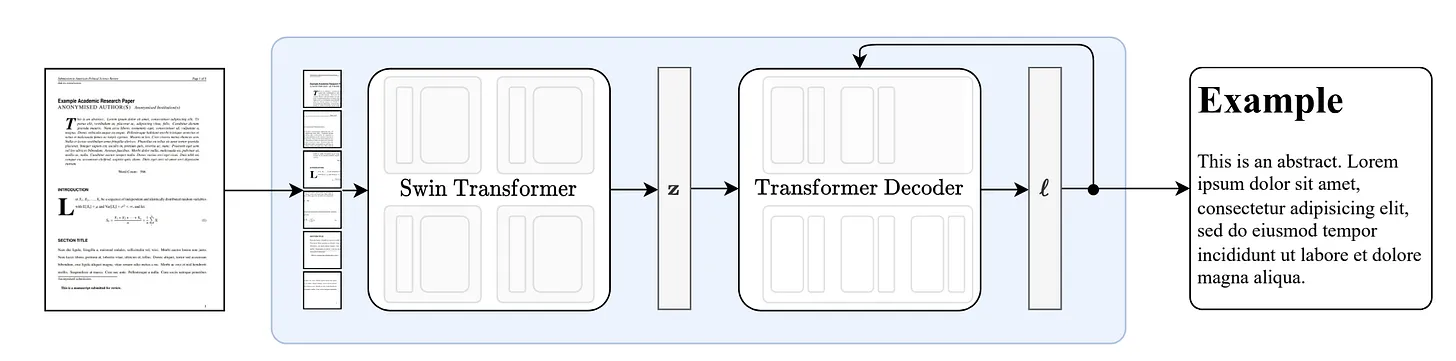

Understanding Nougat’s Architecture

At its core, Nougat is a Visual Transformer model made to handle the OCR challenges found in scientific papers. Instead of just reading text line by line, Nougat combines image understanding with text generation, so it can turn complex pages into clean, structured text.

The model is composed of two main components:

-

Vision Encoder – Takes a PDF page as an input image and extracts rich visual features, capturing layout and structural details.

-

Text Decoder – Translates those visual features into structured markup text, preserving equations, formatting, and other complex elements.

Nougat leverages Hugging Face’s VisionEncoderDecoderModel, with pre-trained weights provided under facebook/nougat-base. This encoder–decoder setup allows the model to bridge the gap between raw PDF images and machine-readable scientific text.

Source: Data Processing Pipeline

Setup the environment

To get started with Nougat, we import the required libraries:

from transformers import NougatProcessor, VisionEncoderDecoderModel, infer_device

from datasets import load_dataset

import torch

from PIL import Image

from huggingface_hub import hf_hub_download

from typing import Optional, List

import io

import fitz

from pathlib import Path

Loading the Nougat Model

We load the pre-trained Nougat model and processor:

# Load the processor and model

processor = NougatProcessor.from_pretrained("facebook/nougat-base")

model = VisionEncoderDecoderModel.from_pretrained("facebook/nougat-base")

# Move model to respective device (GPU if available)

device = infer_device()

model.to(device)

Processing PDFs with Nougat

Step 1: Rasterizing PDF Pages

Before we can process a PDF with Nougat, we need to convert each page into an image. We’ll use PyMuPDF (fitz) for this:

def rasterize_paper(

pdf: Path,

outpath: Optional[Path] = None,

dpi: int = 96,

return_pil=False,

pages=None,

) -> Optional[List[io.BytesIO]]:

"""

Rasterize a PDF file to PNG images.

Args:

pdf (Path): The path to the PDF file.

outpath (Optional[Path]): Output directory for images.

dpi (int): The output DPI. Defaults to 96.

return_pil (bool): Return PIL images instead of saving to disk.

pages (Optional[List[int]]): Pages to rasterize. If None, all pages.

Returns:

Optional[List[io.BytesIO]]: PIL images if return_pil is True.

"""

pillow_images = []

if outpath is None:

return_pil = True

try:

if isinstance(pdf, (str, Path)):

pdf = fitz.open(pdf)

if pages is None:

pages = range(len(pdf))

for i in pages:

page_bytes: bytes = pdf[i].get_pixmap(dpi=dpi).pil_tobytes(format="PNG")

if return_pil:

pillow_images.append(io.BytesIO(page_bytes))

else:

with (outpath / ("%02d.png" % (i + 1))).open("wb") as f:

f.write(page_bytes)

except Exception:

pass

if return_pil:

return pillow_images

Step 2: Implementing Custom Stopping Criteria

Nougat uses a custom stopping criteria during text generation to avoid repetitive outputs:

from transformers import StoppingCriteria, StoppingCriteriaList

from collections import defaultdict

class RunningVarTorch:

def __init__(self, L=15, norm=False):

self.values = None

self.L = L

self.norm = norm

def push(self, x: torch.Tensor):

assert x.dim() == 1

if self.values is None:

self.values = x[:, None]

elif self.values.shape[1] < self.L:

self.values = torch.cat((self.values, x[:, None]), 1)

else:

self.values = torch.cat((self.values[:, 1:], x[:, None]), 1)

def variance(self):

if self.values is None:

return

if self.norm:

return torch.var(self.values, 1) / self.values.shape[1]

else:

return torch.var(self.values, 1)

class StoppingCriteriaScores(StoppingCriteria):

def __init__(self, threshold: float = 0.015, window_size: int = 200):

super().__init__()

self.threshold = threshold

self.vars = RunningVarTorch(norm=True)

self.varvars = RunningVarTorch(L=window_size)

self.stop_inds = defaultdict(int)

self.stopped = defaultdict(bool)

self.size = 0

self.window_size = window_size

@torch.no_grad()

def __call__(self, input_ids: torch.LongTensor, scores: torch.FloatTensor):

last_scores = scores[-1]

self.vars.push(last_scores.max(1)[0].float().cpu())

self.varvars.push(self.vars.variance())

self.size += 1

if self.size < self.window_size:

return False

varvar = self.varvars.variance()

for b in range(len(last_scores)):

if varvar[b] < self.threshold:

if self.stop_inds[b] > 0 and not self.stopped[b]:

self.stopped[b] = self.stop_inds[b] >= self.size

else:

self.stop_inds[b] = int(

min(max(self.size, 1) * 1.15 + 150 + self.window_size, 4095)

)

else:

self.stop_inds[b] = 0

self.stopped[b] = False

return all(self.stopped.values()) and len(self.stopped) > 0

This stopping criteria monitors the variance in the model’s output logits and stops generation when it detects repetitive patterns, which is crucial for handling long scientific documents.

Step 3: Generate Transcription

Let’s create a function that combines all the steps to transcribe a PDF page:

def transcribe_image(image, processor, model, device):

"""

Transcribes a single image using the Nougat model.

Args:

image (PIL.Image.Image): The input image.

processor: The Nougat processor.

model: The Nougat model.

device: The device to run the model on.

Returns:

str: The transcribed text.

"""

pixel_values = processor(image, return_tensors="pt").pixel_values

outputs = model.generate(

pixel_values.to(device),

min_length=1,

max_length=4500,

bad_words_ids=[[processor.tokenizer.unk_token_id]],

return_dict_in_generate=True,

output_scores=True,

stopping_criteria=StoppingCriteriaList([StoppingCriteriaScores()]),

)

generated_sequence = processor.batch_decode(

outputs[0],

skip_special_tokens=True,

)[0]

generated_sequence = processor.post_process_generation(

generated_sequence,

fix_markdown=False

)

return generated_sequence

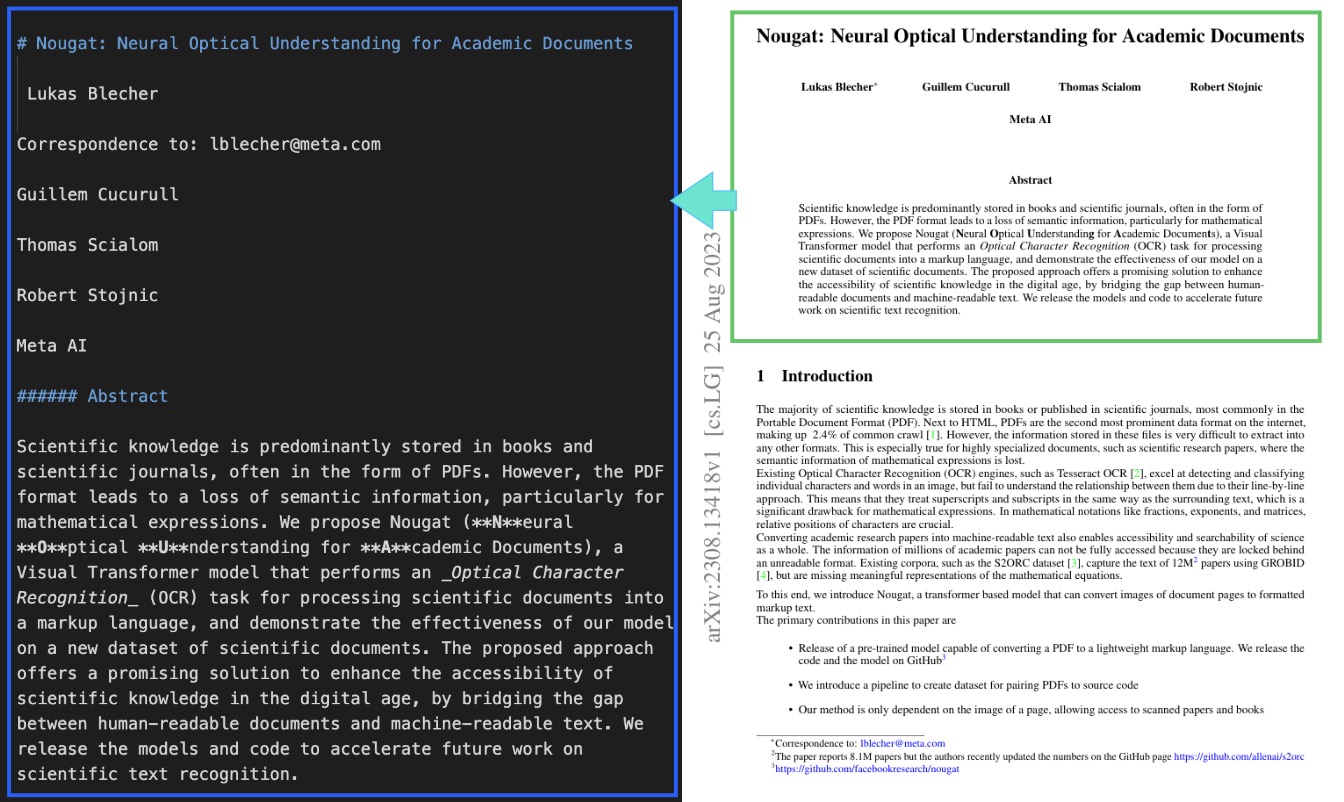

Examples

Let’s walk through a quick example of using Nougat on a scientific paper:

# Download a sample PDF

filepath = hf_hub_download(repo_id="ysharma/nougat", filename="input/nougat.pdf", repo_type="space")

# Convert PDF pages to images

images = rasterize_paper(pdf=filepath, return_pil=True)

# Process the first page

image = Image.open(images[0])

transcribed_text = transcribe_image(image, processor, model, device)

print(transcribed_text)

When we run this on the first page, Nougat produces structured text that captures both the content and layout of the document:

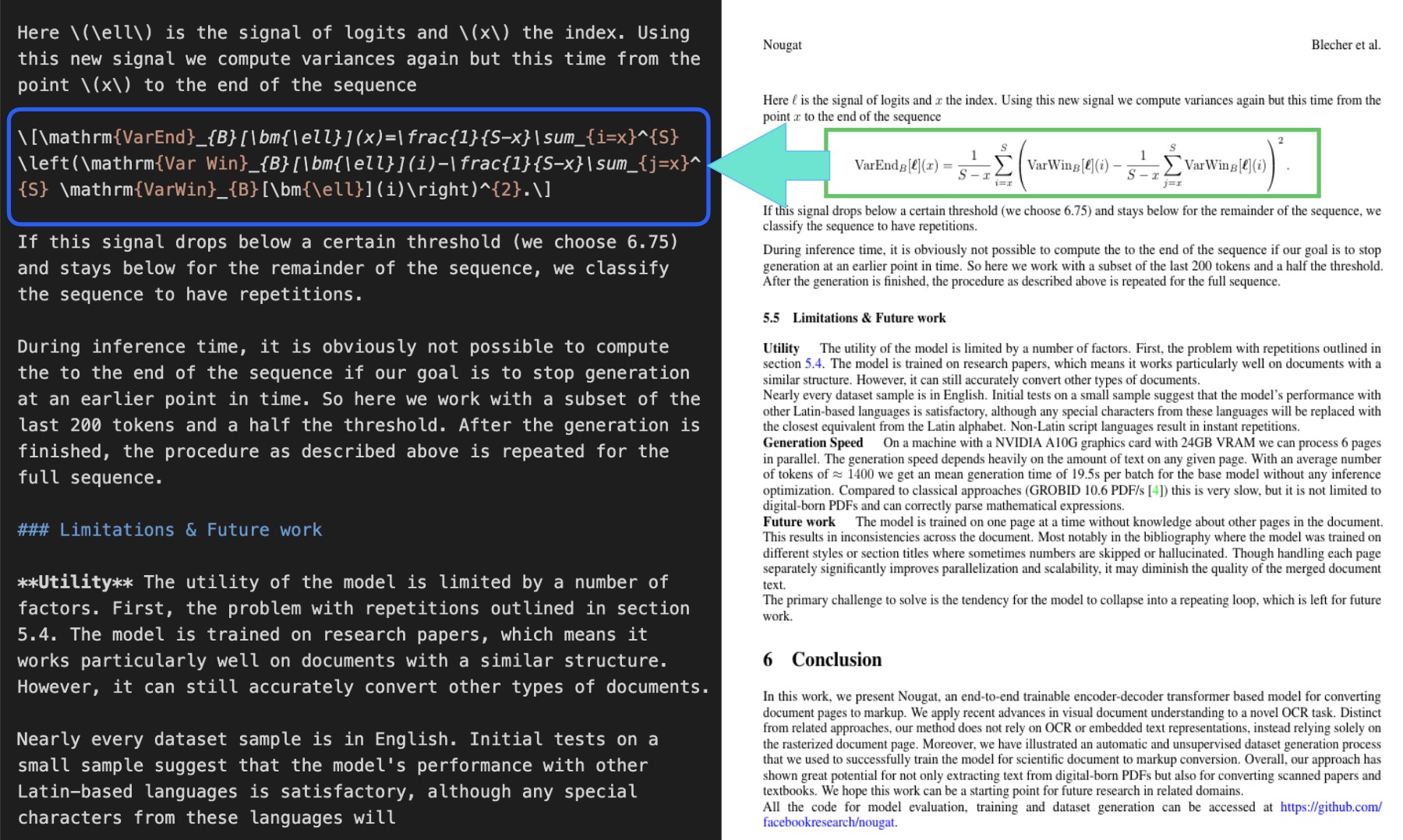

Handling Mathematical Expressions

One of Nougat’s standout features is its ability to transcribe mathematical equations with high accuracy. For example, let’s process a page that contains complex math:

# Process a page with mathematical equation

image = Image.open(images[8])

math_text = transcribe_image(image, processor, model, device)

print(math_text)

Output:

As you can see, Nougat correctly transcribes the complex mathematical expressions using LaTeX notation, making them machine-readable while preserving their semantic meaning.

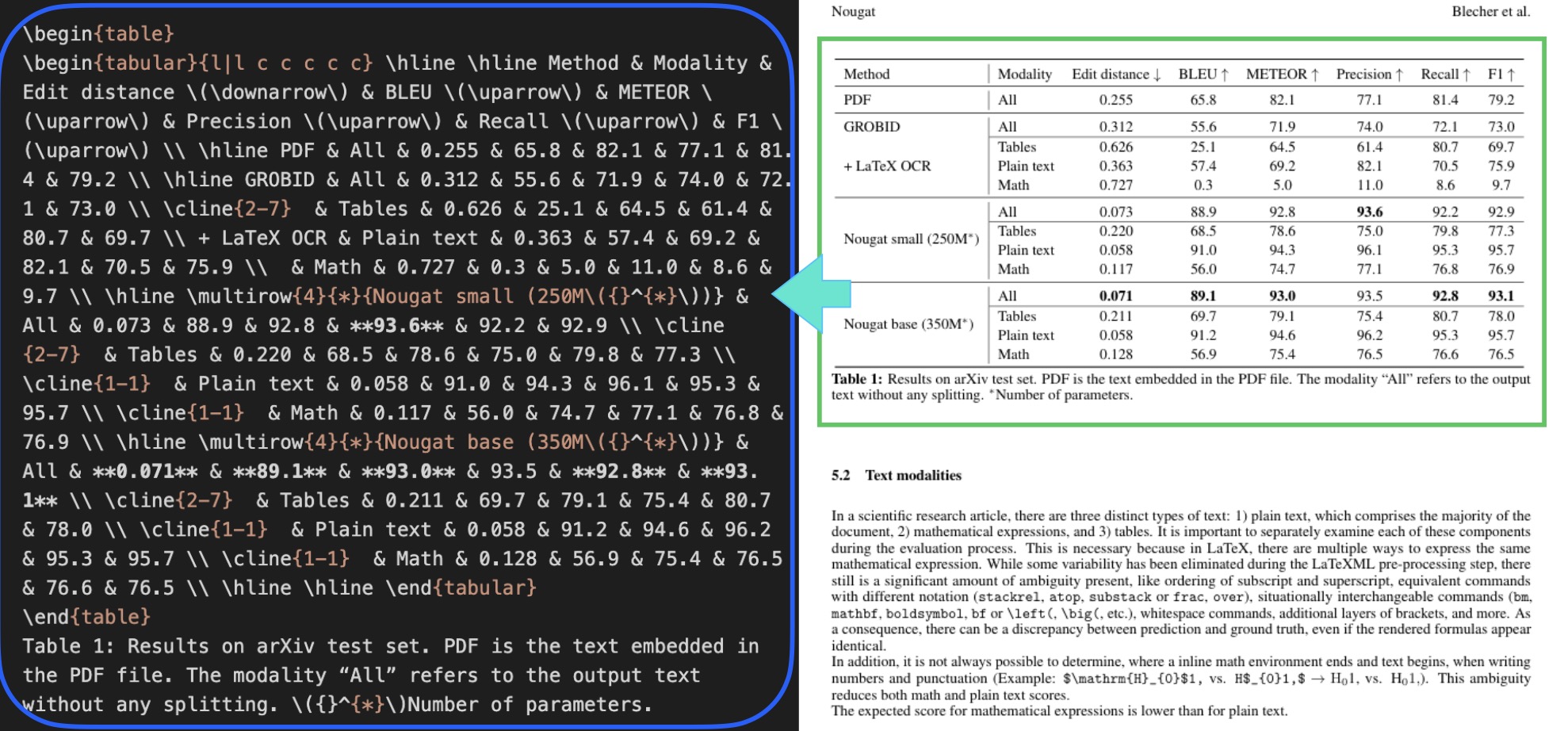

Parsing Tables

Scientific papers often contain structured tables, which are usually very hard for OCR tools to process correctly. Nougat handles them surprisingly well.

# Process a page with a table

image = Image.open(images[6]) # Example: page with a table

table_text = transcribe_image(image, processor, model, device)

print(table_text)

The model converts tables into a readable text or markup form, keeping rows and columns intact so the data can be easily extracted for further analysis.

Challenges and Limitations

While Nougat is a big step forward in scientific document parsing, it’s not without challenges:

-

Language Limitations: The model is mainly trained on English. It can handle some other Latin-based languages, but support is limited.

-

Mathematical Expression Ambiguity: In LaTeX, the same formula can be written in different ways. This can cause differences between Nougat’s output and the original source.

-

Boundary Detection: Distinguishing where inline math ends and plain text begins can sometimes be tricky, which may affect accuracy.

-

Document Structure: Nougat works best on research papers and similar structured documents. It can process other formats too, but with less reliability.

As the paper points out, “The expected score for mathematical expressions is lower than for plain text,” reflecting these inherent difficulties.

Applications

Despite its limitations, Nougat have many applications for working with scientific literature:

-

Knowledge Extraction: Convert PDFs into structured data that can be analyzed or stored in databases.

-

Accessibility: Make scientific content available in formats that work better with screen readers and assistive tools.

-

Search and Indexing: Turn equations and text into searchable content, improving retrieval across large collections of papers.

-

Data Mining: Enable large-scale analysis by transforming thousands of PDFs into machine-readable text.

Conclusion

Nougat is a big step forward for working with scientific papers, especially those that include tricky layouts, equations, and tables. It helps turn PDFs made for people to read into text that machines can understand, making scientific knowledge easier to search, analyze, and reuse.

Because Nougat can handle not only plain text but also math formulas and tables, it’s a powerful tool for researchers, publishers, and anyone dealing with academic documents. As the model improves, we can expect it to get even better at parsing and understanding complex papers.