Understanding LumberChunker: A Step-by-Step Guide to a Novel Chunking Method for Improving RAG Workflow

Table of contents

Introduction

Handling long documents—like books, legal texts, reports, or narrative stories—is a big challenge in modern natural language systems. Large Language Models (LLMs) are powerful, but they have limits on how much text they can process at once (context windows). Also, when you feed them huge texts directly, important information can get lost or diluted.

To solve this, many systems use a “retrieve + generate” setup often called Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). In RAG, you first retrieve the most relevant passages from a large text corpus, and then feed those passages plus the user’s query into a model to produce an answer. This reduces hallucinations and grounds the model in real content.

One overlooked but crucial step in RAG is*how you break the long documents into smaller units**, or chunks. If you split poorly—say, cutting in the middle of an idea or mixing different topics—your retrieval module might miss relevant parts or retrieve chunks full of noise.

LumberChunker is a new approach that addresses that. Instead of chopping text evenly, it uses an LLM to decide where topic boundaries naturally occur, thereby creating semantically coherent chunks. In other words, the model itself helps figure out where one “idea” ends and another begins. This leads to better retrieval performance and more relevant context feeding into downstream tasks.

Background

To fully understand LumberChunker, it helps to review a few key ideas and related work:

Chunking and Its Importance in Retrieval

-

What is chunking? Chunking is splitting a long text into smaller parts (chunks) so that downstream systems can process them. In embedding-based retrieval, each chunk is turned into a vector and stored in an index. When you ask a question, you match it to chunk vectors and retrieve the most relevant ones.

-

Why chunk well?

- If chunks are too short, you might lose context or break up coherent information.

- If chunks are too long, they can mix several topics, making embeddings less focused.

- Poor chunks harm retrieval accuracy: the right answer might be split across chunks, or irrelevant parts might dominate.

- Many chunking methods are simple heuristics (fixed size, sentences, paragraphs) or use embedding-based heuristics (split where embedding similarity drops).

-

Trade-offs

- More chunks → more storage and slower retrieval

- Bigger chunks → risk of mixing topics

- Sophisticated chunking methods cost more compute or rely on extra models

Studies (e.g. Chroma’s report) have shown that chunking choice can influence retrieval performance by up to 9% in recall. So, chunking isn’t just a small preprocessing step — it can strongly affect the pipeline’s success.

Semantic / Dynamic Chunking

-

Static vs semantic chunking Traditional chunkers split by fixed token count or by natural delimiters (sentences, paragraphs). Semantic chunking tries to segment based on meaning—i.e., split when topics change. Some methods use embeddings to detect change points.

-

LLMs as chunkers The idea behind LumberChunker is that LLMs, which understand semantics and discourse, can decide where the boundary should lie. The method prompts the LLM to look at a group of paragraphs and pick which paragraph is the turning point. That becomes a chunk boundary.

-

GutenQA benchmark To evaluate these chunking strategies, the authors introduce GutenQA — a dataset of narrative books from Project Gutenberg, chunked with LumberChunker. It contains 3,000 “needle-in-a-haystack” type QA pairs across 100 books. ([arXiv][1]) The idea is that many questions are about small details, so good chunking is crucial to retrieving the exact passage.

-

Baseline methods The authors compare LumberChunker against:

- Paragraph-level chunking

- Recursive fixed-size chunking

- Semantic chunking based on embedding distances

- Proposition-based chunking (atomic statements)

The results show that LumberChunker outperforms these baselines in retrieval metrics and downstream RAG performance.

Here’s a detailed, clear, and well-structured “Methodology” section for your LumberChunker blog — written in plain, non-technical language but still accurate to the paper and your Jupyter pipeline.

Methodology

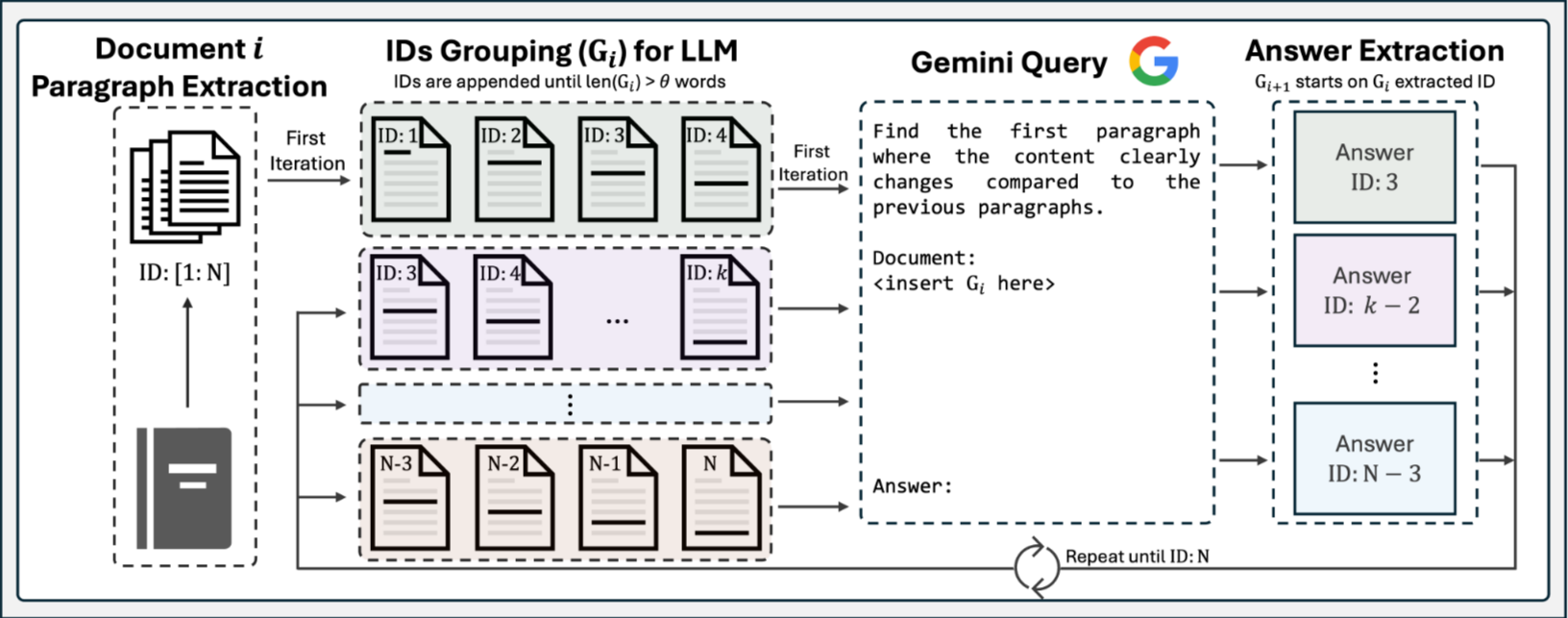

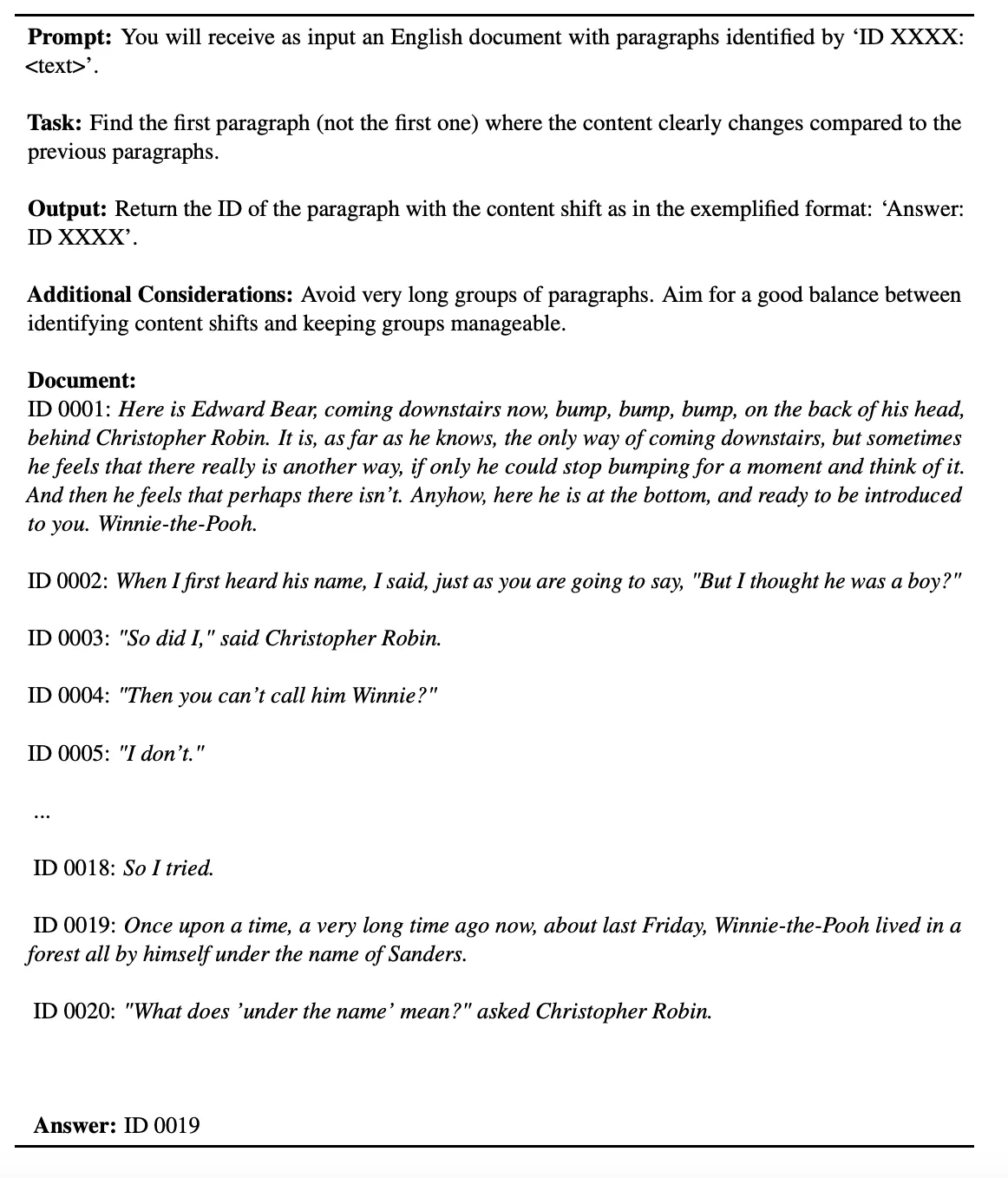

“LumberChunker Gemini Prompt example for the book: Winnie the Pooh by A. A. Milne.”

The core idea behind LumberChunker is to let a Large Language Model (LLM) decide where one topic ends and another begins — instead of using a fixed-size rule like “split every 500 tokens.” Below is the complete step-by-step process of how LumberChunker works internally and how we use it in the retrieval pipeline.

Overview of the Pipeline

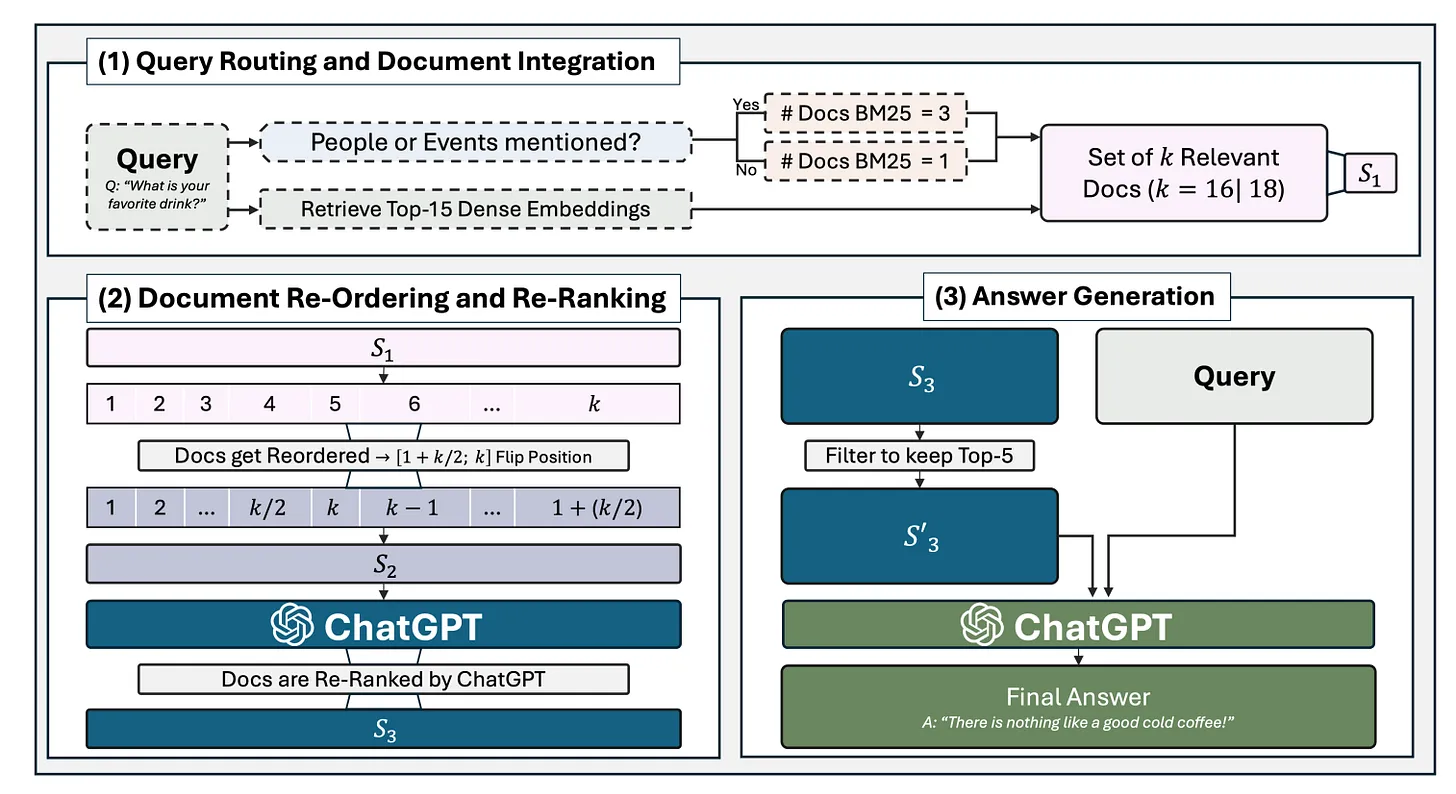

The LumberChunker pipeline has two main parts:

- Chunking Stage – where long documents are divided into semantically meaningful chunks using an LLM.

- Retrieval Stage – where each chunk is embedded, stored, and later matched with user questions to find the most relevant parts of the document.

This design helps Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) systems get cleaner, contextually complete pieces of text to work with.

Case Study

Step 1: Initial Segmentation

The document (e.g., a book or report) is first split into paragraphs. Each paragraph gets a unique ID so the system can track it later.

Example:

Paragraph 1 → “Anna looked out the window, lost in thought.”

Paragraph 2 → “She wondered when she would see Vronsky again.”

...

These paragraphs act as the smallest meaningful units of the text.

Step 2: Group Formation

Next, LumberChunker forms paragraph groups — small batches of paragraphs that stay under a token limit θ (for example, 512 or 1024 tokens).

This grouping ensures that:

- The input size fits within the LLM’s context window.

- The LLM can analyze several paragraphs together to detect natural topic changes.

So instead of feeding the whole book to the model, we feed it manageable pieces.

Step 3: Content Shift Detection (LLM Step)

This is the key innovation.

Within each paragraph group, the LLM analyzes the content and identifies where the topic naturally shifts — for example, when the scene changes, a new event starts, or a character transition happens.

For each group, the LLM is prompted with an instruction like:

“Read the following paragraphs and decide where the content meaningfully shifts to a new topic.”

The LLM then outputs something like:

“The content shifts after Paragraph 4.”

That paragraph becomes the chunk boundary — the end of one chunk and the start of another.

This process repeats until the entire document has been chunked.

Creating the Chunked Dataset (GutenQA Example)

In this project, LumberChunker was used to chunk 100 narrative books from Project Gutenberg to create a new dataset called GutenQA. Each chunk is stored with:

- The book name

- The chunk text

- The chunk ID

- The related question-answer pairs (for retrieval testing)

Example structure:

| Book Name | Chunk | Chunk ID | Question | Answer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anna Karenina | “Anna looked out the window…” | 1234 | “Who does Anna love?” | “Vronsky” |

This structure allows us to evaluate retrieval quality later.

Embedding Generation (Retriever Setup)

Once chunks are created, they are converted into numerical embeddings using a dense retriever model — in this case, Facebook’s Contriever.

Steps:

-

Load pretrained Contriever model and tokenizer:

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained('facebook/contriever') model = AutoModel.from_pretrained('facebook/contriever') -

Tokenize the text:

inputs_chunks = tokenizer(chunks, padding=True, truncation=True, return_tensors='pt') -

Pass through the model and mean-pool token embeddings to get one vector per chunk:

embeddings = model(**inputs_chunks).last_hidden_state sentence_emb = embeddings.mean(dim=1)

Each question and chunk is represented as a vector in the same semantic space.

Similarity Search (Retrieval Stage)

For every question, we compute cosine similarity between its embedding and all chunk embeddings:

similarity_scores = torch.nn.functional.cosine_similarity(

question_embeddings.unsqueeze(1),

chunk_embeddings.unsqueeze(0),

dim=-1

)

The top-k most similar chunks (usually k=3 or 5) are retrieved as the best matches. This forms the retrieval output — the foundation for answering questions or feeding into a RAG system.

Why This Works

- The LLM recognizes semantic flow, not just token counts.

- Chunks end where ideas end — so retrieval returns meaningful, self-contained passages.

- The model avoids “fragmentation” (splitting connected information) and “bloating” (mixing topics).

Overall, this makes downstream RAG systems more grounded, concise, and accurate.

Results & Insights

Once the LumberChunker pipeline was applied to long-form documents like Anna Karenina and other Project Gutenberg books, the benefits became easy to see — both quantitatively and qualitatively.

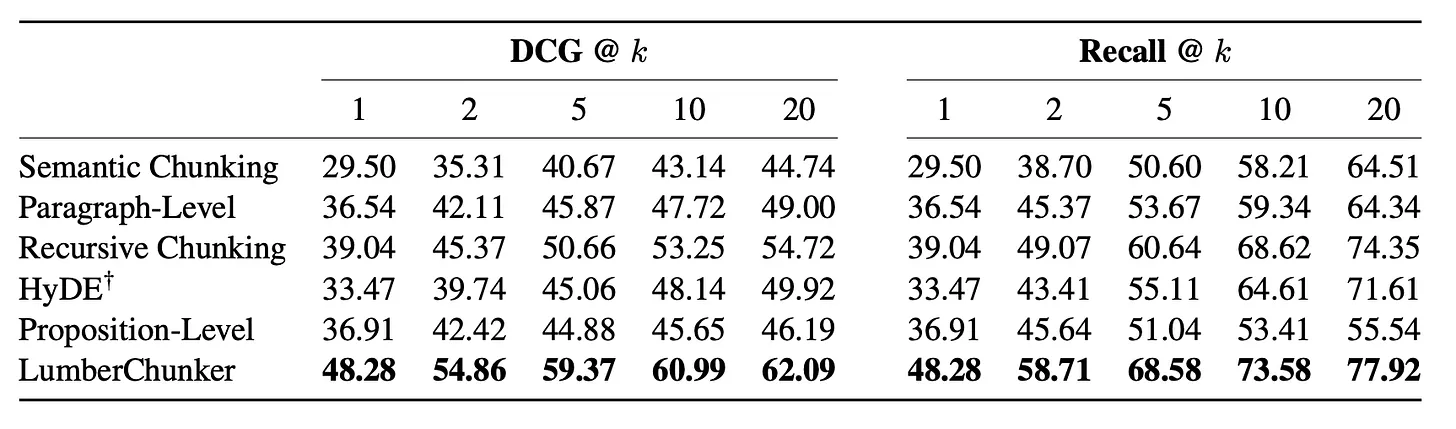

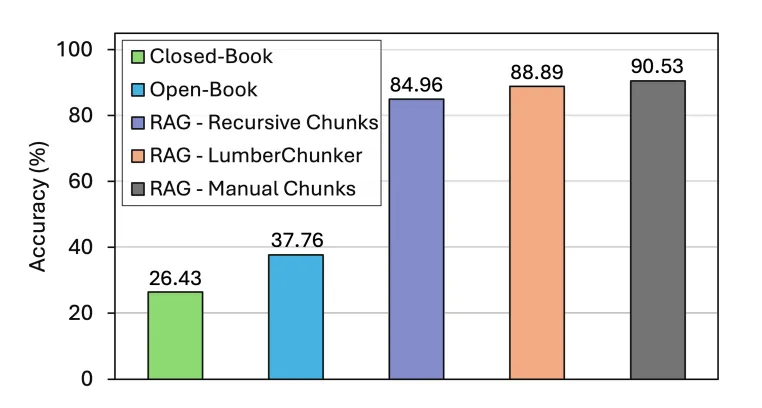

Quantitative Results

In the original study, LumberChunker was tested on the GutenQA benchmark — a dataset built from 100 narrative books, containing thousands of “needle-in-a-haystack” question-answer pairs. Each method was evaluated by how well its chunks helped a retriever (like Facebook Contriever) locate the right passage.

Key metrics used:

- Recall@k – checks whether the correct answer chunk appears in the top k retrieved results.

- DCG@k (Discounted Cumulative Gain) – rewards correct answers that appear higher in the ranking.

Results:

- LumberChunker achieved roughly a 7.4 % improvement in DCG@20 compared to strong baselines such as fixed-size and embedding-based chunkers.

- It also maintained better recall at smaller k values, meaning the correct chunk was often found among the very top results.

These results show that topic-aware chunking can make retrieval systems noticeably more accurate — even when using the same retriever model.

Qualitative Insights

When you inspect the retrieved text chunks, the difference becomes intuitive:

| Question | Chunk Type | Example Observation |

|---|---|---|

| “Who does Anna fall in love with?” | LumberChunker Chunk | The passage cleanly covers the chapter where Anna meets Vronsky — all relevant sentences stay together. |

| Fixed-Size Chunk | The chunk cuts off mid-scene, splitting crucial dialogue between two pieces. |

This demonstrates that LumberChunker preserves narrative context — scenes, character interactions, and ideas remain intact.

As a result:

- Retrieval models “see” more complete meaning per chunk.

- Fewer unrelated words dilute the embeddings.

- Downstream RAG models receive more coherent context, which leads to clearer, more factual answers.

Key Insights

From experiments and observation, several important takeaways came:

-

Chunk quality outweighs quantity. More chunks don’t always help; meaningful boundaries matter far more than total count.

-

Topic-aligned segmentation improves semantic focus. When each chunk covers one coherent topic, embeddings become sharper and retrieval ranking becomes more stable.

-

LLMs understand narrative structure. By leveraging an LLM for segmentation, the system naturally detects scene changes, character shifts, and conceptual breaks that statistical methods miss.

-

Better chunking generalizes. LumberChunker isn’t limited to novels — the same idea can apply to technical reports, research papers, or long-form news articles where context boundaries are subtle but important.

Limitations

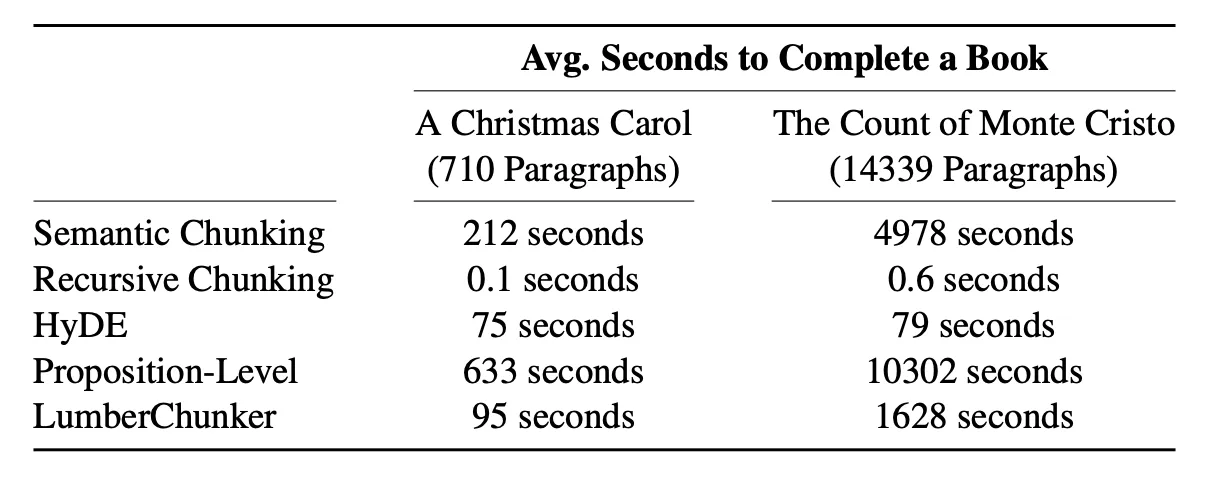

While LumberChunker represents a strong step forward in document chunking, it still has a few limitations that researchers and practitioners should keep in mind.

- Computational Cost

Because LumberChunker relies on prompting an LLM for each paragraph group, it is more computationally expensive than fixed-size or heuristic chunkers. For very large corpora, this can increase both time and API cost, especially when using high-end models like GPT-4 or Claude for segmentation.

- Dependence on LLM Quality

The effectiveness of topic detection depends heavily on how well the chosen LLM understands the text. A weaker or smaller model might misjudge topic boundaries, leading to inconsistent chunk sizes or misplaced cuts. The quality of the prompt also influences results — small phrasing changes can affect how the LLM identifies shifts.

- Evaluation Complexity

Evaluating chunk quality is non-trivial. A higher retrieval score doesn’t always mean the chunk boundaries are ideal — some may still capture mixed topics but rank high due to word overlap. There’s no single objective metric that fully captures semantic boundary accuracy.

- Domain Transfer

LumberChunker was tested mainly on narrative text (fiction, stories). Topic transitions in these domains are often clear and sequential. However, in technical, legal, or conversational documents, topic shifts can be subtle, and the same method might need additional tuning or domain-specific prompting.

Conclusion

The LumberChunker retrieval pipeline is a great demonstration of how dense retrievers like Contriever can handle long-text question answering. It provides a clean workflow — from loading data and embeddings to computing similarity and retrieving the top answers.

Although it’s not perfect (lacking fine-tuning and generative steps), still, the insights it brings to document segmentation are valuable and forward-looking.

Note:

LumberChunker shows how machines can read, chunk, and recall stories — just like flipping through the right pages of a book when someone asks a question.